BLOG

Categories

Vergüenza y adopción: una guía para criar a los hijos con empatía

Vergüenza. Es una sensación incómoda que la mayoría de nosotros conocemos. Se encuentra en los lugares más profundos dentro de nosotros, en las partes de nosotros mismos que rara vez visitamos y deseamos ignorar.

¿Y si no pudiéramos ignorarlo? ¿Qué pasaría si viviéramos en un mundo donde la vergüenza no solo estuviera profundamente arraigada en nuestros sistemas, sino que también fuera utilizada como táctica por otros para alentarnos y motivarnos a hacer las cosas que no queríamos hacer?

La verdad es que muchos de nosotros hemos experimentado este escenario exacto en las formas en que hemos sido criados. Para aquellos en la constelación de adopción, la realidad de la vergüenza es demasiado familiar.

Este blog explica cómo la vergüenza afecta a todos en la adopción y ayudará a los padres con algunas de estas preguntas:

- ¿Cómo puedo disciplinar a mi hijo sin avergonzarlo?

- ¿Cómo le enseño valores a mi hijo?

- ¿Cómo le enseño responsabilidad a mi hijo?

- ¿Cómo ayudo a mi hijo a expresar emociones?

¿Qué tiene de malo la vergüenza?

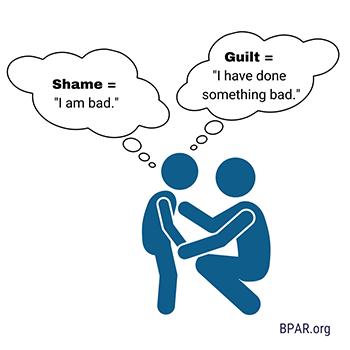

La vergüenza está en el centro de nuestro sentido del yo. Es la sensación de que somos inherentemente desagradables, que somos indignos y que no merecemos conexión. La vergüenza se integra en nuestro ser de una manera que impacta directamente en el desarrollo de nuestra autoestima y autoestima. La vergüenza a menudo está estrechamente asociada con sentimientos de culpa, pero estos dos sentimientos son cualitativamente diferentes. La culpa es el sentimiento de que uno es responsable de un delito, generalmente con respecto a un comportamiento socialmente inaceptable o un delito. Cuando experimenta vergüenza, una persona cree “soy malo”, en lugar de experimentar culpa, donde una persona cree: “He hecho algo malo”.

La culpa puede ser una emoción productiva en el sentido de que motiva a las personas a actuar de manera socialmente deseable. Es una emoción aprendida que está influenciada por aquellos en nuestro entorno, comenzando con nuestras primeras relaciones de cuidador y reforzadas por nuestras comunidades educativas, espirituales o sociales. Cuando la empatía se entrega frente a la culpa, los niños son capaces de internalizar los valores de sus relaciones de apego de manera que les ayuden a animarlos a tomar decisiones positivas.

Las experiencias prolongadas o repetidas de vergüenza sin la oportunidad de reparación pueden hacer que los niños se sientan abrumados por la vergüenza y, posteriormente, los llevarán a evitar experimentar vergüenza a toda costa. Esto a veces puede manifestarse como un cumplimiento excesivo e hipervigilancia para realizar tareas de manera que complacen a los demás. Alternativamente, esto puede parecer una completa incapacidad para aceptar la responsabilidad de las malas acciones de uno, porque si asumen la responsabilidad, eso significa que son “el error”.

Vergüenza en la adopción

La vergüenza es un problema importante en la adopción, y afecta profundamente a todos los afectados por ella. Para aquellas personas que han sido adoptadas, la separación del padre biológico puede suscitar muchas preguntas. Como los niños tienden a ser egocéntricos, pueden internalizar la creencia de que su separación es su responsabilidad, que son inherentemente desagradables. Aquellos que han sido adoptados también pueden experimentar vergüenza por ser diferentes de sus familias adoptivas o comunidades más amplias. Para los padres biológicos, existe una larga historia de vergüenza y culpa asociada con el secreto de colocar a un niño o el juicio de otros por sus decisiones. Para los padres adoptivos, pueden haber internalizado la vergüenza en torno a la infertilidad o las pérdidas que pueden haberlos llevado a la adopción. La vergüenza puede ser magnificada para aquellos en la constelación de adopción que se ven afectados por el trauma relacional, la violencia, el abuso, la negligencia, o aquellos que han navegado por sistemas o individuos que han retenido información, coaccionado o manipulado.

Vergüenza en la crianza de los hijos

Es natural y esperado que los niños actúen de manera socialmente indeseable y cometan muchos errores a medida que aprenden y exploran el mundo que los rodea. Como padres, el objetivo no es eliminar por completo estos errores, sino apoyar y guiar a nuestros hijos a tomar las mejores decisiones posibles.

Muchos de nosotros hemos experimentado vergüenza en las formas en que hemos sido criados. A menudo, sin querer, la vergüenza se puede obtener a través de las formas en que hemos aprendido a enseñar y guiar a nuestros hijos. Cuando nosotros, como cuidadores, estamos abrumados o más allá de nuestros límites, podemos enviar mensajes a nuestros hijos sobre su personalidad, sus sentimientos o sus necesidades en nuestros intentos de dirigirlos.

Algunas frases comunes pueden incluir mensajes sobre:

Quién es su hijo:

En lugar de “Eres tan lento, ¿te darías prisa?”, intenta esto: “¡Oh! Estamos llegando tarde. Pensemos en cómo podemos usar una herramienta (temporizador, cuenta regresiva) para asegurarnos de hacer nuestra cita a tiempo”.

Cómo se siente su hijo:

En lugar de “Deja de llorar, estás bien. Eso no fue gran cosa“, intenta esto: “Veo que estás llorando, está bien sentirse triste. Estoy aquí para escuchar si quieres decirme lo que pasó“.

Lo que su hijo necesita:

En lugar de “¿No ves que estoy trabajando? Ve a la otra habitación“, prueba esto: “Parece que necesitas mi atención. Estoy trabajando en este momento, así que no puedo jugar contigo, pero puedes sentarte a mi lado en silencio“.

Crianza de los hijos con empatía

El primer paso para criar a los hijos con empatía es tener compasión por ti mismo como padre. Es importante recordar que como cuidadores, no siempre lo haremos bien. Antes de que pueda presentarse y conectarse con su hijo, también debe presentarse por sí mismo. Esto puede parecer como hacer una pausa y respirar profundamente antes de responder a su hijo o esto puede parecer pedir ayuda para satisfacer sus propias necesidades. Estamos constantemente bombardeados con información que nos invita a juzgarnos y criticarnos como padres; pero recuerde, esto es solo otra forma de vergüenza. Enfréntate a eso con profunda amabilidad por ti mismo y por quién quieres ser como padre.

Al criar con empatía, el objetivo es comprender los sentimientos y necesidades subyacentes de su hijo y establecer límites claros sin juicio o crítica. El objetivo final es ayudar a su hijo a sentirse escuchado y comprendido. Tratar a su hijo con respeto y amabilidad en la forma en que establece límites ayudará a desarrollar la capacidad de empatía de su hijo y fomentará una conexión más profunda dentro de su relación. A continuación se presentan algunas estrategias para probar.

Separa el comportamiento de la persona. Al establecer un límite o responder a un conflicto, ayude a su hijo a separar sus acciones de lo que es como persona. En última instancia, queremos que los niños entiendan la diferencia entre su sentido de sí mismos y sus elecciones. Trate de recordarle a su hijo su valor, y luego llame claramente el comportamiento que no está bien. Por ejemplo, “Te amo. Está bien estar enojado, y no está bien golpear a tu hermano”.

Modele el comportamiento deseado. Los niños aprenden una cantidad increíble al observar a los adultos en sus vidas. Repetirán los comportamientos que ven y aprenderán a inhibir los comportamientos en consecuencia. Trate de ser coherente entre lo que les enseña verbalmente y cómo usted, como padre, existe en el mundo. Por ejemplo, si gritar es un comportamiento inaceptable para su hijo, considere con qué frecuencia muestra la misma reactividad. Si su enseñanza y modelado son incongruentes, los niños reciben mensajes contradictorios sobre lo que se espera de ellos.

Fomentar la expresión emocional. Esté dispuesto a involucrar a su hijo en la exploración de sus experiencias emocionales. Proporcionar validación ayuda a los niños a sentirse vistos y comprendidos. Para los niños pequeños, esto puede parecer inicialmente un reflejo de lo que ves: “Veo que estás apretando los puños, parece que te sientes enojado. Está bien sentirse enojado”. Esté abierto al diálogo sobre lo que le está sucediendo emocionalmente a su hijo y considere compartir con ellos cómo sus comportamientos lo han impactado a usted o a otros. Por ejemplo, “Me siento frustrado cuando le arrojas juguetes a tu hermana”. Está bien hacerle saber a su hijo cómo se siente en respuesta a sus acciones. Queremos que los niños entiendan el impacto que tienen y desarrollen la capacidad de comprender las perspectivas de los demás. Sin embargo, cuando comparta su experiencia emocional con un niño, asegúrese de enfatizar que los sentimientos son sobre el comportamiento, no sobre el niño.

Esté abierto a comunicarse. El secreto perpetúa la vergüenza al reforzar la creencia de que algo está fuera de los límites. Esté disponible y abierto para discutir todos y cada uno de los pensamientos, sentimientos o inquietudes que su hijo pueda compartir. Considere el uso de un lenguaje apropiado para su edad en la forma en que responde, pero modele una cultura de apertura dentro de su relación.

Refleja quiénes quieres que sean. Todos los niños aprenden quiénes son dentro de sus relaciones con los demás. La forma en que respondemos e interactuamos con los niños da forma a sus creencias sobre sí mismos. Cuando los padres reflejan la creencia de que un niño es digno, adorable, fuerte, capaz, valiente, etc., los niños también comenzarán a creer esas cosas sobre sí mismos. Cuando creemos y asumimos que un niño actuará mal o se comportará mal, ese niño también internalizará eso como verdad, dejando poca motivación para tratar de cambiar la creencia de sus padres. Ver más allá del comportamiento de un niño y comprender la necesidad que lo impulsa, es una buena manera de encontrar algo de compasión y recordarnos a nosotros mismos que nuestros hijos son buenos, incluso cuando cometen errores.

Conexión de valor sobre castigo. Enseñar a un niño que una acción o comportamiento no es aceptable se puede hacer reconociendo las necesidades de su hijo, empatizando con su experiencia y estableciendo un límite. Por ejemplo, “Veo que necesitas mi atención ahora mismo. Me preocupo por ti y sé que es difícil esperar, pero estoy hablando por teléfono. No está bien empujarme. Configuremos un temporizador para 5 minutos para que sepas que hablaré contigo entonces”. No es necesario castigar a un niño para comunicar que cometió un error. Los niños pueden responder al castigo con un cumplimiento excesivo y tratando de complacer, o pueden reaccionar con ira y desafío. De cualquier manera, lo que se internaliza es un sentido magnificado de vergüenza y un deseo de evitar esos sentimientos, no una capacidad para tomar decisiones positivas.

Durante los momentos de crianza estresante, podemos cometer errores. Criar a los hijos con empatía se trata de profundizar la comprensión, no se trata de la perfección. Se necesita una enorme cantidad de energía para regularnos como padres para que podamos presentarnos a nuestros hijos. El esfuerzo que ponga en conectarse y comprender a su hijo finalmente le permitirá comenzar a verse a sí mismo como digno y capaz de tomar buenas decisiones a lo largo de su vida. Tener el apoyo de las relaciones y la comunidad mientras navegas por este viaje es muy importante. Si está buscando construir más conexiones para usted, BPAR ofrece una serie de recursos para padres, incluidos grupos de apoyo continuos para padres.

RECENT POSTS

Bringing and keeping families together!