BLOG

Categories

Shame and Adoption — A Guide to Parenting with Empathy

Shame. It’s an uncomfortable feeling that most of us know. It sits in the deepest places within us, in the parts of ourselves we rarely visit and wish to ignore.

What if we couldn’t ignore it? What if we lived in a world where shame was not only embedded deeply within our systems, but it was also used as a tactic by others to encourage and motivate us to do the things we didn’t want to do?

The truth is, many of us have experienced this exact scenario in the ways we have been parented. For those in the adoption constellation, the reality of shame is all too familiar.

This blog explains how shame affects all in adoption and will help parents with some of these questions:

- How do I discipline my child without shaming?

- How do I teach my child values?

- How do I teach my child responsibility?

- How do I help my child express emotions?

What’s Wrong With Shame?

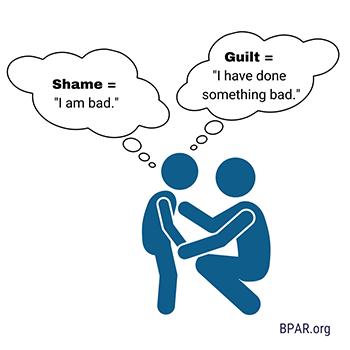

Shame is at the core of our sense of self. It is the feeling that we are inherently unlovable, that we are unworthy, and that we are undeserving of connection. Shame integrates itself into our beings in a way that directly impacts the development of our self-esteem and self-worth. Shame is often closely associated with feelings of guilt, but these two feelings are qualitatively different. Guilt is the feeling that one is responsible for wrongdoing, usually in regard to socially unacceptable behavior or a crime. When experiencing shame, a person believes “I am bad,” as opposed to experiencing guilt, where a person believes, “I have done something bad.”

Guilt can be a productive emotion in that it motivates people to act in socially desirable ways. It is a learned emotion that is influenced by those in our environment, beginning with our earliest caregiver relationships and reinforced by our educational, spiritual, or social communities. When empathy is delivered in the face of guilt, children are capable of internalizing the values of their attachment relationships in ways that help encourage them to make positive choices.

Prolonged or repeated experiences of shame without the opportunity for repair can cause children to feel overwhelmed by shame, and subsequently will lead them to avoid experiencing shame at all costs. This can sometimes manifest as overcompliance and hypervigilance to performing tasks in ways that please others. Alternatively, this can look like a complete inability to accept responsibility for one’s wrongdoings, because if they do take accountability, that means that they are “the mistake.”

Shame in Adoption

Shame is a significant issue in adoption, and it deeply affects all those touched by it. For those individuals who have been adopted, separation from the birth parent may stir a lot of questions. As children tend to be egocentric, they may internalize a belief that their separation is their responsibility—that they are inherently unlovable. Those who have been adopted may also experience shame around being different from their adoptive families or wider communities. For birth parents, there exists a long history of shame and guilt associated with the secrecy of placing a child or judgment from others for their decisions. For adoptive parents, they may have internalized shame around infertility or the losses that may have led them to adoption. Shame can be magnified for those in the adoption constellation who are impacted by relational trauma, violence, abuse, neglect, or those who have navigated systems or individuals who have withheld information, coerced, or manipulated them.

Shame in Parenting

It is natural and expected that children will act in socially undesirable ways and make many mistakes as they learn about and explore the world around them. As parents, the goal is not to completely eliminate these mistakes, but to support and guide our children to making the best decisions possible.

Many of us have experienced shame in the ways we have been parented. Often unintentionally, shame can be elicited through the ways we have learned to teach and guide our children. When we as caregivers are overwhelmed or beyond our limits, we may send messages to our children about their personality, their feelings, or their needs in our attempts to direct them.

Some common phrases might include messages about:

Who your child is:

Instead of “You are so slow, would you hurry up!?” try this: “Oh! We are running late. Let’s think about how we can use a tool (timer, countdown) to make sure we make our appointment on time.“

How your child feels:

Instead of “Stop crying, you’re fine. That wasn’t a big deal,” try this: “I see you are crying, it is okay to feel sad. I’m here to listen if you want to tell me what happened.”

What your child needs:

Instead of “Can’t you see that I’m working? Go to the other room,” try this: “It looks like you need my attention. I am working right now, so I can’t play with you, but you can sit next to me quietly.”

Parenting with Empathy

The very first step in parenting with empathy is having compassion for yourself as a parent. It is important to remember that as caregivers, we will not always get it right. Before you can show up and connect with your child, you must also show up for yourself. This might look like pausing and taking a deep breath before responding to your child or this might look like asking for help in order to get your own needs met. We are constantly bombarded with information that invites us to judge and criticize ourselves as parents; but remember, this is just another form of shame. Confront that with deep kindness for yourself and who you want to be as a parent.

In parenting with empathy, the goal is to understand the underlying feelings and needs of your child and set clear limits absent of judgement or criticism. The ultimate goal is to help your child feel heard and understood. Treating your child with respect and kindness in how you set limits will help build your child’s capacity for empathy and foster a deeper connection within your relationship. Below are some strategies to try.

Separate the behavior from the person. When setting a limit or responding to a conflict, help your child separate their actions from who they are as a person. Ultimately we want children to understand the difference between their sense of self and their choices. Try reminding your child of their worth, and then clearly calling out the behavior that is not okay. For example, “I love you. It is okay to be mad, and it is not okay to hit your brother.”

Model the desired behavior. Children learn an incredible amount from watching the adults in their lives. They will repeat behaviors they see, and will learn to inhibit behaviors accordingly. Aim for consistency between what you teach them verbally and how you as the parent exist in the world. For example, if yelling is an unacceptable behavior for your child, consider how often you display the same reactivity. If your teaching and modeling are incongruent, children receive mixed messages about what is expected of them.

Encourage emotional expression. Be willing to engage your child in exploring their emotional experiences. Providing validation helps children feel seen and understood. For young children, this may initially look like reflecting what you see: “I see you are clenching your fists, it looks like you might feel mad. It is okay to feel mad.” Be open to dialogue about what is happening for your child emotionally and consider sharing with them how their behaviors have impacted you or others. For example, “I feel frustrated when you throw toys at your sister.” It is okay to let your child know how you feel in response to their actions. We do want children to understand the impact they have and build a capacity to understand others perspectives. When sharing your emotional experience with a child, however, be sure to emphasize that the feelings are about the behavior, not the child.

Be open to communicate. Secrecy perpetuates shame by reinforcing a belief that something is off limits. Be available and open to discuss any and all thoughts, feelings, or concerns that your child may share. Consider the use of age-appropriate language in how you respond, but model a culture of openness within your relationship.

Reflect who you want them to be. All children learn who they are within their relationships to others. How we respond and interact with children shapes their beliefs about themselves. When parents reflect a belief that a child is worthy, lovable, strong, capable, brave, etc., children will start to believe those things about themselves, too. When we believe and assume that a child will act out or behave poorly, that child will also internalize that as truth, leaving little motivation to try to change their parents belief. Seeing past a child’s behavior and understanding the need that drives it, is a good way to find some compassion and remind ourselves that our children are good, even when they make mistakes.

Value connection over punishment. Teaching a child that an action or behavior is not acceptable can be done by recognizing your child’s needs, empathizing with their experience, and setting a limit. For example, “I see that you need my attention right now. I care about you and I know it is hard to wait, but I am on the phone. It is not okay to push me. Let’s set a timer for 5 minutes so you know I will talk to you then.” It is not necessary to punish a child in order to communicate that they made a mistake. Children may respond to punishment by over-compliance and attempting to please, or they may react with anger and defiance. Either way, what is internalized is a magnified sense of shame and a desire to avoid those feelings, not an ability to make positive choices.

During moments of stressful parenting, we might make mistakes. Parenting with empathy is about deepening understanding, it is not about perfection. It takes an enormous amount of energy to regulate ourselves as parents so that we can show up for our children. The effort you put into connecting with and understanding your child will ultimately allow them to begin to see themselves as worthy and capable of making good choices across their lifetime. Having the support of relationships and community while you are navigating this journey is so important. If you’re seeking to build more connections for yourself, BPAR offers a number of resources for parents, including ongoing parent support groups.

RECENT POSTS

Bringing and keeping families together!